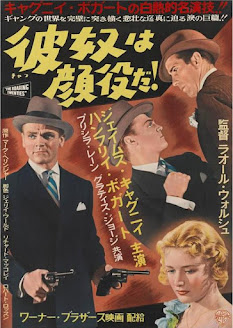

Casino manager Johnny O'Clock (1947) (Dick Powell) awakens to a mess of trouble. Nelle Marchettis (Ellen Drew), the wife of his business partner,a Pete (S. Thomas Gomez) has sent him an expensive watch with a tender endearment engraved on it. Harriet Hobson (Nina Foch), the hat check girl in his casino, is distraught - her lover, police detective Chuck Blayden (Jim Bannon) has tired of her. Add to this, Police Inspector Koch (Lee J. Cobb) is nosing around his hotel lobby. Johnny's difficulties are just beginning.

This is a film that requires the kind of concentration that you have in a movie theatre, which makes watching it on a television a bit of a commitment. Several of us commented that we did appreciate the opportunity to run the film back and rewatch certain scenes to clarify our questions. But the plot is dense, and though it all ties together in the end, there are periods when you feel like something has been dropped from the action.

Dick Powell is excellent as the titular hero of the piece, a man with a heart who camouflages it with brusque repartee. This was his third appearance as a noir leading man, and he commands the screen. The introductory scenes to the film outline the complexity of the man who now calls himself Johnny O'Clock - there is a subtlety to this opening that negates the fact that these are the background aspects of of the film.

Evelyn Keyes is also convincing as Nancy Hobson, the sister of the sad Harriet. We felt that during much of the film, Ms. Keyes was able to keep you in doubt as to her motives and next actions, which worked well for the character. Her autobiography noted the constant changes that were being made to the script by first time director Robert Rossen (TCM article). We wondered if Mr. Rossen's neophyte status as a director (and the ongoing alterations) caused some of the density in the storyline (AFI catalog).

The film opens with Lee J. Cobb visiting the hotel residence of Johnny but it's really not clear WHY he is there. We learn that Johnny, though possessing a slew of aliases, has never had any real problems with the law; and the series of crimes that occur within the film have not yet happened. It's not clear if Inspector Koch is aware of Detective Blayden's side deals, but having Koch there does give us much of that background information that the director/screenwriter Rossen want to convey to the audience. Mr. Cobb is good in the part (though Ms. Keyes noted that he had a penchant for stealing scenes by chomping on his ever present cigar).

Several other actors deserve mention. Ellen Drew is fiendish as the straying wife who has her eye on Johnny; she reminds one of a wild cat - purring one minute and snarling the next. She's given excellent support by Thomas Gomez as her braggart husband - and Johnny's partner. His passion for his wife is evident - as is his jealousy for her obviously wandering eye.

John Kellogg as Charlie, Johnny's friend and major domo is also worthy of a mention. Charlie seems on the up-and-up, and like Ms. Keyes, keeps his real motivations a secret until the end of the film. Mr. Kellogg spent much of his movie career in small, often uncredited parts. He moved easily into television in the 1950s, where he worked until 1990 (he'd started his film career in 1940, after doing some stage work) in shows such as Bonanza, Gunsmoke, and The Untouchables. He died of Alzheimer's Disease in 2000 at the age of 83.

Nina Foch has such a tiny part, but she is quite lovely as the sad-eyed Harriet. She'd made My Name is Julia Ross (a starring role) two years earlier, but that was a B movie, and Ms. Foch rarely got the opportunity to star in A movies. She makes the most of her small amount of screen time - you remember the character throughout the film, thanks to her excellent performance.

Bosley Crowther was unimpressed by the film in his New York Times review: "another of those smoldering exhibitions of gambling-joint jealousy and greed...", while a more recent review Richard Brody in The New Yorker called it "terse and taut film noir." Perhaps had director Rossen had a tad more experience, he would have been able to tighten the film a bit; the nearly two hour length leads to some redundancy that we found unnecessary.

Lux Radio Theatre did an episode in May of 1947, with Dick Powell and Marguerite Chapman. In summary, we enjoyed the film, in spite of its faults; it's an opportunity to see some good actors, portraying very intriguing characters. We'll leave you with a trailer: